Classes began this past week, and with the start of a new scholastic year, certain expectations have been put on the children in the Villa. Last year a number of students failed their grade and will be repeating the same classes. In order to avoid a similar occurrence, the administration and mamás have decided to remove the televisions from the six houses that had them, demand a regular study period, and require perfect attendance (except in cases of illness). One result of this exigency has been a large increase in the number of children who come to the Reading Room. In the morning, as many as twelve children at once are in the Room reading or asking to borrow books. This week I am planning to start a program that rewards the children for their interest in the written word. Each time that they complete a book, they will be able to put their name and the book they read in a list. After a certain number of books, they will receive small prizes. I remember Book It from my childhood and how I used to love eating personal pan pizzas at Pizza Hut as a reward. What is most encouraging to me is that the children come and ask me to read at all hours of the day. Regardless if I am in the middle of basketball practice or individual time in a house, the children often will plea with me to give them the key to the Reading Room. I tell them to ask Daisy for the key, but they insist on using mine. Although the children are generally very respectful of the rules in the Reading Room, it is still necessary to have someone in charge of checking-out and returning books. For now, the only problem is having someone for this purpose in the Reading Room at all hours of the day. The children have two hours in the morning with me and two hours in the afternoon with Gray, but there are three hours in the late afternoon in which the Room is closed. This week, I hope to find someone in the Villa who will be able to help out during this time, so that a desire to read will continue to grow in the children.

Wednesday, February 21, 2007

A week ago, a group of six leaders from the Villa’s Scouts program, Sonia, Rosi, Claudia, Pamela, Tatiana, and I, met early Sunday morning in a nearby suburb of Cochabamba. In our weekly leaders’ meeting, Sonia had told us about a project that she had been working with for the past year in Quillacollo that gives support to street children in the area. One of the biggest problems in starting programs like these to help such children, she said, was that public officials do not know how many or in what areas these children live. She asked for our help in taking a census of these children to determine where aid could best be utilized.

So, at seven on Sunday morning, I boarded a bus with Claudia to take the hour trip to Quillacollo. During the journey, Claudia and I practiced the questions that we were to ask “street children” between five and eighteen years old. Even after we arrived in Plaza Bolívar and were briefed on how to identify and interview the children, I had my doubts about who was a proper candidate to solicit. Sonia told me not to worry and to use my best judgment.

We then divided up into small groups and headed toward different sections of Quillacollo. With my twenty-two interviews and coupons (for the children to receive free bananas and milk in the main plaza), I headed toward the central marketplace. When we arrived, Claudia, Pamela, and I split up and agreed to meet back in four hours. I began scanning the area for prospective interviewees and quickly located a young girl selling fruit on the side of the street. I approached her, introduced myself, explained what I was doing, and asked if she would participate. At first she seemed confused and hesitant, even after I told her that she could get free bananas and milk. But when I told her that I also had some gum for all those who helped out, she immediately agreed. I admit, my method may have been a little coercive, but hopefully the anonymous information that she provided me with outweighs any adverse affects she may have felt.

We began the interview, and she told me that she was seven years old and helped her mother in the market on weekends. When I asked her where her mother was, she just waved in a general direction. Her three younger brothers were playing nearby in the plaza but without adult supervision. The interview sheet required me to ask some personal questions about her family, such as if she had experienced physical abuse at home. However, I did not feel comfortable posing such questions to a child who I had just met, and so for the rest of the day I avoided the more invasive interrogatories. I thought if the goal of the census was to identify the quantity and location of street and troubled children, the mere fact that a seven-year-old girl was alone and selling fruit in the street was enough information to qualify her as someone who needed aid. I completed the interview by talking about school and her favorite subjects and giving her the food coupon and gum. She seemed very pleased to receive both and even more excited when I told her that the gum was from the United States. I thanked her for her time and wished her well in her vending.

Glad to have the first interview out of the way and without any problems, I continued searching for more young children. I found three brothers playing on a curb nearby and asked if they wanted to participate. In unison, they replied, “Sí, sí, yo primero.” We finally agreed that we would go in chronological order of age, starting with the youngest. After the first interview, in which the six-year-old boy told me that he sold vegetables in the street on Sundays with his brothers, the next two were straightforward. The oldest brother (10) mentioned that their father had abandoned the family when he was five, and that their mother and grandmother cared for them. The regrettable circumstance of one-parent households is an all too common reality in Bolivia, and as the children talked about the absence of a father in their own lives, they did so as if it were nothing out of the ordinary. Once again, I tried to end the interview with a short chat about something light. The boys mentioned Spider Man, so I rolled with it and talked about villains and friends of the superhero. The youngest insisted on acting out Spider Man’s web slinging attacks, and we all had a laugh when he fell into a pile of papayas. I gave the children the compensation for the interview and told them to keep practicing their Spider Man moves.

Four down and feeling good about my quick progression, I continued around the market square and encountered a ten-year-old girl selling peaches and oranges. In between sells, she agreed to the interview, and we started with some basic questions. But about half-way through the interview, a man to her right starting asking me questions about when and how the children of Quillacollo would receive benefits from this project. I told him that I honestly did not know but that it was first necessary to have an idea of how many and what kind of children lived in need. Not impressed with the offer of bananas and milk in the central plaza, he said that I needed to leave. I asked him, “Why, are you her father?” He replied, “Yes, and I would like you to leave now.” So I asked the girl, “Is this your father?” She told me yes, and I walked away. Perhaps it was the fact that I am a gringo, or more exactly, with my interviewer badge, glasses, and pale skin I looked like one of the many Mormon converters in Cochabamba. Regardless, the information from this interview was destined for the trashcan.

Luckily, I did not have any more experiences as confrontational as this one. Four or five indigenous women refused my offers for interviews with their children, but I had expected to get rejected more times than I did. In addition, I had some interesting encounters. I interviewed a Quechua woman and her six-year-old son, me only speaking Spanish to her and her only speaking Quechua to me. Although I know the whole of two words in this native tongue, I was able to conduct a fairly comprehensible interview through gestures and support from the child. In another situation, I walked five blocks with a nine-year-old boy pushing a loaded cart while asking him questions about his family life. In yet another instance, I went to a videogame arcade and conducted two interviews with boys who were battling each other in Mortal Kombat. In between shouts of victory and defeat, I found out that they sell ice cream on the streets on the weekends and share a small room with their two younger brothers. But they were clearly more interested in exacting Fatalities on one another than in the interview.

After nearly five hours of talking to a variety of children, youths, and parents, I was exhausted. I met up with the rest of the Scout group in the central plaza, and we shared our experiences. Together, we had accomplished more than 120 interviews and encountered many different personalities. Compiled with the help of other groups of volunteers, we had achieved more than 500 interviews. When and how the needy children of Quillacollo will be helped, I do not know. But on the bus ride back to the center of Cochabamba, I felt that I had at least contributed to the process that would eventually result in better lives for these children.

Wednesday, February 07, 2007

With the summer vacation coming to a close, the mamás of the Villa decided to give the children an uncommon treat: an adventure to the highest city in the world. After several weeks of planning and several days of waiting for roadblocks and violence to end in Cochabamba, a trip to Potosí was finally achieved. Leaving on a Monday night around 10 o’clock (in typical Bolivian fashion, the bus we commissioned arrived two hours late), fifty-two eager children, seven mamás, Gualberto, and an awkward gringo packed into a “flota” designed for thirty-six passengers. Upon loading numerous blankets and gigantic suitcases in the storage compartments below, we crammed ourselves into the overwhelmed vehicle. In order to make space for everyone, mattresses were laid in the aisle, and the littlest children sprawled out in the last remaining empty spaces. Despite the ridiculously crowded conditions (three people to every two seats), the children remained quite animated. We spent the first hour of the bus ride singing spiritual songs (of which the children know dozens) and laughing at our contortioned bodies struggling to find a comfortable seated position.

Unfortunately, the road to Potosí is neither short nor straight. After about the fourth hour of the fourteen-hour journey along endless windy roads to an altitude of 4300 meters, the children grew restless. Without a bathroom in the bus and no convenient or safe place to stop in the middle of the night with numerous young children, the ride became a test of attrition. Instead of sleeping comfortably on their mattresses, the young children cried out in hunger and pain. Daybreak could not have come sooner, and when we finally stopped at a small village (still about seven hours from Potosí), the children made a dash to the bathrooms. After “filling” ourselves with tea and a piece of bread with butter, we headed back to the mobile prison that awaited us. Luckily, a sleepless night and a bit of nourishment proved to be enough to put most of the children into a peaceful slumber.

At noon, we arrived at the bus terminal in Potosí and waited for Gualberto to get transportation to our hostel. But our wait was in vain, as Gualberto returned to tell us that our reservations had been given away to another group. Oh, Bolivia. So we spent another two hours in the bus terminal trying to arrange other lodging (no small feat for sixty people).

Gualberto was able to eventually get us a place in a retreat area for church groups about twenty kilometers outside of the city. We then packed all of our stuff into three vans and backtracked for thirty minutes. Upon arriving at the church, the children were less than pleased and began to argue about who would sleep in each room (the altitude and fatigue were not helping the cause). But we were able to get everyone to settle down and eat a late afternoon soup in the mess hall. After our “early-bird special,” Gualberto told the children that we were going to turn in for the night. As it was five o’clock in the afternoon, I thought that he might be joking. However, he was not, and the children did not put up much of a fuss about sleeping when three hours of daylight (i.e. playtime) remained.

Gualberto was able to eventually get us a place in a retreat area for church groups about twenty kilometers outside of the city. We then packed all of our stuff into three vans and backtracked for thirty minutes. Upon arriving at the church, the children were less than pleased and began to argue about who would sleep in each room (the altitude and fatigue were not helping the cause). But we were able to get everyone to settle down and eat a late afternoon soup in the mess hall. After our “early-bird special,” Gualberto told the children that we were going to turn in for the night. As it was five o’clock in the afternoon, I thought that he might be joking. However, he was not, and the children did not put up much of a fuss about sleeping when three hours of daylight (i.e. playtime) remained. I followed nine boys up the stairs to our room and climbed into my bottom bunk bed. The boys were willing to put on their pajamas and brush their teeth, but once they had settled into bed, typical boy behavior took over. This was one of the few independent sleepovers that they had ever had, and the teasing and shenanigans ensued for about two hours. I did not want to deprive them of their fun, but when girls from the next room came to complain of the rowdiness, I had to calm them down…or at least try. They were quiet long enough for me to fall asleep, but apparently not enough so to satisfy the mamás and tías in the adjacent rooms. I am told that on two occasions one of them came in to chastise the boys. However, it’s all hearsay to me, because few things could have disturbed me after the previous twenty-four hours.

In the morning, I awoke to the elated shouts of the boys repeating, “Vamos a las aguas termales!” Forget about the hundreds of years of rich history in Potosí, a day at the hot springs had been promised to the children and for them that was the most anticipated adventure in our trip. While the location of the hostel was inconvenient for exploring the city of Potosí, it was perfect for our day at the hot springs. We took an easy fifteen-minute walk along the road and arrived at a recreational complex. The hot springs were not the bubbling pools surrounded by lush vegetation that I had expected. Rather, the “hot springs” consisted of one large swimming pool with an enormous tarp shading it (the power of the Potosian sun is not to be taken lightly). I personally was not too thrilled about the pool, but the children did not hesitate to leap in with joy.

However, after surfacing, all but a few children quickly scrambled to the side of the pool. I realized that they did not know how to swim. I was not alone, though, and another adult in the pool tried to teach them. After several frustrating attempts and fearful screams, the children pretty much gave up on learning. Even so, they still enjoyed throwing balls to each other and inventing different water games.

However, after surfacing, all but a few children quickly scrambled to the side of the pool. I realized that they did not know how to swim. I was not alone, though, and another adult in the pool tried to teach them. After several frustrating attempts and fearful screams, the children pretty much gave up on learning. Even so, they still enjoyed throwing balls to each other and inventing different water games. After a full day at the pool, it was time to go back to our hostel for another early dinner. The children ate quickly, and then we went to play tag in the courtyard. After an hour or so, Gualberto told us that it was time to get ready for bed. It was only seven o’clock, but we were going to get an early start in the morning to visit the old coin mint and the famous mines of Potosí. Luckily, the boys in my room were much calmer this night and did not protest when the lights went out at eight.

The trip to the coin mint was well worth the six o’clock wakeup. Built during the time of Spanish rule in Bolivia, it provided enormous wealth to the conquistadors who exploited the immense silver deposits in the hills of Potosí. In the seventeenth century, Potosí was one of the largest and richest cities in the world.

This wealth came at the cost of many African and indigenous slaves, who were used to extract silver from Cerro Rico and make it into coins and jewels. The coin mint that we visited revealed part of this tragic story. Heavy cranks, wheels, and other machinery were lasting reminders of the countless deaths suffered by the slaves who toiled under the supervision of Spanish overseers. Once a mold was made, each coin was individually stamped with the use of a sledgehammer. It is estimated that millions of coins were made in this one site.

This wealth came at the cost of many African and indigenous slaves, who were used to extract silver from Cerro Rico and make it into coins and jewels. The coin mint that we visited revealed part of this tragic story. Heavy cranks, wheels, and other machinery were lasting reminders of the countless deaths suffered by the slaves who toiled under the supervision of Spanish overseers. Once a mold was made, each coin was individually stamped with the use of a sledgehammer. It is estimated that millions of coins were made in this one site.Although the coin mint was the dreadful house for the production of Spanish silver for many years, the true sorrow of Potosí is found in the mines of Cerro Rico.

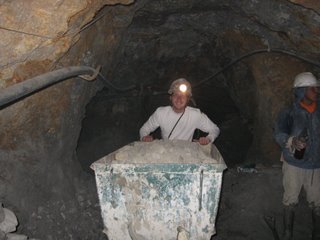

For the last 450 years, these mines have been bled of almost all their profitable minerals. Some estimates say that over eight million people have died over this time. Apart from the danger of falling rocks and dynamite explosions, the prevalence of silicosis, a pulmonary disease that eventually causes the lungs to burst, amongst those who work in the mines provides an additional threat. It is hard to imagine how awful these conditions truly are, but we were able to see a glimpse of this depressing life on a guided tour of the mines.

For the last 450 years, these mines have been bled of almost all their profitable minerals. Some estimates say that over eight million people have died over this time. Apart from the danger of falling rocks and dynamite explosions, the prevalence of silicosis, a pulmonary disease that eventually causes the lungs to burst, amongst those who work in the mines provides an additional threat. It is hard to imagine how awful these conditions truly are, but we were able to see a glimpse of this depressing life on a guided tour of the mines. Gualberto, four mamas, twelve children, and I took a ride up to Cerro Rico in the afternoon to visit the mines. Upon arriving at the base, we bought coca leaves, alcohol, cigarettes, and dynamite (it doesn’t look like the sticks you see in the movies) to give to the miners who often work twelve to fifteen hours a day. We then proceeded up the hill and found two miners who would guide us through the confusing labyrinth. It is not permitted to go without a guide, and for good reason. Once we were inside, it was as if we had entered another world, full of winding tunnels, tracks, and piles of rock. One of our guides told us that it was appropriate to give gifts to every group of miners who we talked to. The first group we encountered were mere boys, probably no older than sixteen. Shy at first, they came shooting out of their holes when we told them that we had soft drinks to share. The way that they gulped down these refreshments would make you think that we had given them something much more precious.

At the next station, about two hundred meters inside the mine, we came to a group of men who were banging away at a sheet of rock. Here we offered them dynamite, coca leaves, and cigarettes. They were happy to receive them, but were hoping for a bottle of alcohol. We told them that all we had were small bottles of rubbing alcohol to offer to El Tío.

Speaking of El Tío, it is worth explaining a little bit about the important role of this deity. El Tío is the miners’ representation of the devil and is thought to be the power that controls the fortune of the miners.

In every mine of Cerro Rico there is a statue of El Tío, and miners come daily to give offerings to him. Whether it be coca leaves, alcohol, or cigarettes, the miners believe that if they do not pay homage to El Tío, they will extract few minerals and may even die in an accident. When we visited El Tío, the mamás (some of whose parents had worked in the mines) were adamant about being respectful to him. In turn, we presented our offerings to El Tío and reflected in silence for several minutes. I then asked to take one of the mama’s pictures with El Tío, and she told me absolutely not. You may take a picture of him alone, but never with anyone else. Regardless of my own beliefs, I certainly did not want to offend traditional practices.

In every mine of Cerro Rico there is a statue of El Tío, and miners come daily to give offerings to him. Whether it be coca leaves, alcohol, or cigarettes, the miners believe that if they do not pay homage to El Tío, they will extract few minerals and may even die in an accident. When we visited El Tío, the mamás (some of whose parents had worked in the mines) were adamant about being respectful to him. In turn, we presented our offerings to El Tío and reflected in silence for several minutes. I then asked to take one of the mama’s pictures with El Tío, and she told me absolutely not. You may take a picture of him alone, but never with anyone else. Regardless of my own beliefs, I certainly did not want to offend traditional practices.

We spent another half-hour in the mines and then got escorted out of the muddy tunnels by our guides. On the way back, I stayed in the back with one of the guides and asked him about life in Cerro Rico. He, twenty-one years old, told me that he had been working for seven years in the mines and made about five dollars per day. Today, almost all of the silver has been extracted from the mines, and only in the deepest, most dangerous parts can you find small deposits. Other less valuable minerals and metals, such as tin, are now the principle extractions from the mines. In the hour and a half that we were in the mines, the heartbreaking existence of those who work there overwhelmed me. The tools and techniques that the miners use today have not changed much from a century ago, and the faces of these workers reveal the rigor of their labor.

We spent another half-hour in the mines and then got escorted out of the muddy tunnels by our guides. On the way back, I stayed in the back with one of the guides and asked him about life in Cerro Rico. He, twenty-one years old, told me that he had been working for seven years in the mines and made about five dollars per day. Today, almost all of the silver has been extracted from the mines, and only in the deepest, most dangerous parts can you find small deposits. Other less valuable minerals and metals, such as tin, are now the principle extractions from the mines. In the hour and a half that we were in the mines, the heartbreaking existence of those who work there overwhelmed me. The tools and techniques that the miners use today have not changed much from a century ago, and the faces of these workers reveal the rigor of their labor. Although I can attempt to describe my brief experience in the mines, I would encourage anyone interested in learning more about Cerro Rico to watch a documentary called “The Devil’s Miner.” You can get it at Blockbuster or on NetFlix, and it is incredibly powerful. After our trip, I showed it to the children in the Villa, and I think that some of them became very appreciative of the life and support that they have at Amistad.

Although I can attempt to describe my brief experience in the mines, I would encourage anyone interested in learning more about Cerro Rico to watch a documentary called “The Devil’s Miner.” You can get it at Blockbuster or on NetFlix, and it is incredibly powerful. After our trip, I showed it to the children in the Villa, and I think that some of them became very appreciative of the life and support that they have at Amistad. The visit to Cerro Rico was a moving and fitting conclusion to our trip to Potosí. The bus ride back to Cochabamba was much more comfortable, as we took a flota with fifty-seats. Interestingly, this larger bus only took nine hours to get back to the Villa. And upon arriving at five in the morning, we were all ready for a long nap. A journey to the highest city in the world can be quite exhausting.

For children in Cochabamba, February marks the end of summer vacation and the beginning of a month-long celebration called Carnaval. While the festivities do not officially begin until the 17th, children all over Bolivia use the 1st of February as the starting date for their reign of terror. Water balloons. They are absolutely everywhere. You cannot walk down any street in Cochabamba without feeling the threat of an armed and lurking delinquent ready to plant you one between the eyes. The youngest lads take it as simple fun, trying, mostly in vain, to hurl an overfilled balloon in the direction of an unsuspecting pedestrian. It’s the young adolescents that you have to be careful with. These misfits ride around in cars with a seemingly limitless arsenal of water balloons, searching for their victims. Walking along a side street on my way back from the Villa one afternoon, I found myself alone in just such a situation. What seemed like a common 1980´s Toyota pickup with four boys straddling the sides of the bed turned out to be a dangerous projectile launcher. The truck slowed down, and the boys began whistling and shouting things about a gringo(me). I knew that I was in the wrong place at the wrong time when the first water balloon narrowly missed my left shoulder and crashed into the wall behind me. This was no warning shot, I quickly discovered, but rather an attempt to injure a “maldito gringo”(again, me). The pieces of broken ice on the pavement betrayed these intentions. With little desire to find out what the next shot might contain within it, I began to run (oddly enough, toward my assailants).

As I passed by the truck, three more bullets fired toward me. Using my best Matrix techniques, I tried to contort my body away from harm. However, I am neither Neo nor Boris, and one of the shots found its mark on my right arm. The sting of the hard(frozen) sphere knocked me off balance and against the wall. Cursing the pain, I sprinted down the street, out-of-range of several more futile hurls. Either they had exhausted their ammo or been sufficiently satisfied with one direct hit, but the boys did not pursue me anymore. I am guessing that it was the latter, because their laughter was audible from a block away.

As I looked down at the red spot on my forearm, I thought to myself, Well it could have been worse. I remembered a story that a fellow American acquaintance had told me about her recent experience with the delinquency of Carnaval. When called over to a stopped car to give directions, she was welcomed with a face full of shaving cream. Another day, while riding on a city bus, I witnessed an unfortunate middle-aged woman get pelted in the side of the head with a water balloon. Lesson: regardless of how hot it may be, this month it is not advisable to lower the window on any public transportation vehicle.

As malicious as these stories may seem, I think they are more of the exception than the rule. Most children carrying water balloons seem more interested in playing with each other than bothering strangers. Who doesn’t love a good water fight? Even so, as the official celebration dates approach, you can be sure that I will be vigilant when in public. Who knows, I might even start packing some heat myself.

Saturday, January 13, 2007

Luckily, the black eye left by the protests and violence in Cochabamba has started to heal. Today, diplomatic negotiations have put an end to the public transportation stoppage, and hopefully any further violence. I was able to leave the Villa for the first time in five days today, and it is nice to see the city recovering from all the disruption. In the Villa, we are now planning to leave on our trip to Sucre and Potosí on Tuesday. The children are very excited and continue to remind me to back my bags. I will try to give another update when we return.

Friday, January 12, 2007

The political stability in Cochabamba has not been so fragile since the 2002 Water War. And after talking to numerous individuals who were involved in that conflict, I am told that the current situation is even worse. Three days ago, protestors from Evo Morales’ political party, MAS, began marching in the Plaza Principal, demanding the resignation of the Cochabamban prefect, Manfred Reyes Villa. Their demands stem from Reyes Villa’s initiation of a referendum in the department of Cochabamba to gain more economic and political autonomy. This proposal of a referendum, organized democratically, has been wholly rejected by the farmers and coca growers of the region. As a form of protest, they set fire to the entrance to the building of Manfred’s office, burned two Prefect cars, blockaded all road exits to and from the city of Cochabamba, and begun threatening violence against any who oppose them. For the last three days, the local police have tried to dissuade these protests by using tear gas, but yesterday the conflict reached its height. With protestors from MAS marching for the resignation of Manfred and a counter-march demanding that democracy be upheld, the police were unable to subdue the mobs. Two people were killed, a coca grower supporting MAS and the seventeen-year-old nephew of Reyes Villa´s secretary supporting a youth counter movement. In addition, there were more than seventy wounded, some very seriously, during yesterday’s events. An indefinite public transportation stoppage has been put in effect, and neither side seems willing to compromise its goals. Surprisingly, in the throes of this crisis, the president of the Republic is off in Venezuela celebrating the inauguration of his good friend, Hugo Chávez. The citizens of Cochabamba continue to cry for an end to the violence and for the direct involvement of Evo in the resolution of the conflict. But as of now, these pleas have fallen on deaf ears.

Luckily in the Villa, we are removed from this heated struggle. However, we have not been able to go to the center of town, even in the Villa’s private cars. No one from the administration came to work today, due to the increased presence of blockades and danger in the city. In addition, the five-day trip that we had planned for the children to visit Sucre and Potosí, the highest city in the world, has been postponed indefinitely. Nevertheless, the morale of the children seems to be unaffected by the conflicts that plague the city. At dinnertime, they are more interested in viewing their favorite soap opera than daily news reports. One of the advantages of being so far from the center of town and inside barbed-wire fences is that it is much easier to block out all that is negative in the world around us. But even so, we wait and hope that an end to this dispute will come soon.

Thursday, January 11, 2007

After nearly a two-month hiatus from my blog, I owe an apology to all of the readers interested in the continued growth of the mission here at Amistad. As we begin this new year, one of my resolutions is to give regular and focused attention to updating the blog. The challenge, of course, is to make a sustained effort for the duration of the year and not merely for several months, as is often the case with this type of resolution.

Anyway, in my absence from the blog, many exciting things have happened here in the Villa. Perhaps the greatest of all of these was the 16th Anniversary celebration of the Mission. On a beautiful Saturday in early December, many of the involved parties in the Mission came together for this unique commemoration. Apart from the children, mamás and tías, and workers and administrators of the Villa, we were blessed to have the company of the staff and beneficiaries of the Mission’s work in Aramasi, former Amistad workers, and most especially, several friends and board members of the Mission from the U.S.

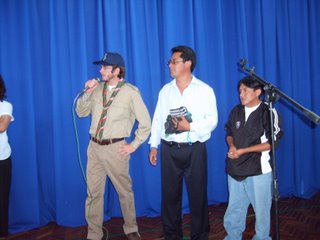

We began the day by introducing our newly-formed Scouts program, which has been an operational project for about two months, with children from the Villa and also from a nearby community participating in group activities every Saturday morning. Children lined up according to their respective groups (Wolf, Pioneers, and Explorers) and saluted in the proper manner the raising of the Scout flag.

Once this introductory activity was completed, we, as leaders of the Scout groups, enlisted the help of the children to seat all of the invited guests outside of Casa San Martín. After several years of disuse, this house was reopened under the direction of a new mamá, Marisa. In order to properly honor this special occasion, Reverend Ken Swanson (a celebrity for these children) introduced the visitors to those who would live in the house. Following this introduction, Reverend Swanson gave a blessing for the prosperity and growth of all who entered into the house, that God protect and keep them in his graces. The mamá and oldest girl of the house then cut the ceremonial red ribbon and entered with the rest of the family, while we all joined in songs of praise led by our choral director, Douglas.

Following the blessing of Casa San Martín, we went to the gymnasium to honor and give plaques to the mamás who work tirelessly to give the children of Amistad a better life. As I have said in previous posts, their dedication should be praised and recognized continuously. They truly are the heart of this institution. The presentation of plaques to the mamás was followed by a moving moment for us all. Vladimir, one of the youths living in the Boys Transition House, approached the microphone and timidly expressed his gratitude for the work and kindness of the members of the Amistad board who had taken the time to visit. As a symbol of this gratitude, he presented each member with a hand-woven pouch that he had personally made over the course of the year. What continues to touch me most about Vladimir’s gifts, however, is the fact that this selfless youth is blind. He, of all the children in the Mission, wanted the supporters of Amistad to understand how much he appreciates them. His efforts and perseverance are an example of one of the many success stories that have and continue to come from children in the Mission.

Following the blessing of Casa San Martín, we went to the gymnasium to honor and give plaques to the mamás who work tirelessly to give the children of Amistad a better life. As I have said in previous posts, their dedication should be praised and recognized continuously. They truly are the heart of this institution. The presentation of plaques to the mamás was followed by a moving moment for us all. Vladimir, one of the youths living in the Boys Transition House, approached the microphone and timidly expressed his gratitude for the work and kindness of the members of the Amistad board who had taken the time to visit. As a symbol of this gratitude, he presented each member with a hand-woven pouch that he had personally made over the course of the year. What continues to touch me most about Vladimir’s gifts, however, is the fact that this selfless youth is blind. He, of all the children in the Mission, wanted the supporters of Amistad to understand how much he appreciates them. His efforts and perseverance are an example of one of the many success stories that have and continue to come from children in the Mission. Once each of the board members had been individually acknowledged and thanked by Vladimir, we settled in to view a theatrical performance by the children of the Villa. The short play, developed over the span of nearly two months, dealt with a dream world inhabited by fantasies and nightmares. Carla, a very intelligent young girl from Casa Esperanza, played the role of the Queen of Dreamland who helped all who entered to realize their goals. After being captured by the cruel inhabitants from the Land of Nightmares, Carla was rescued by two young dreamers (Bárbara from Casa San Francisco and Jhenny from Casa Copacabana) who used laughter to conquer their fears of the nightmares. The play ended with the message that all dreams can come true through hardwork and perseverance and that no impediment, such as a nightmare, is too great to overcome.

Once each of the board members had been individually acknowledged and thanked by Vladimir, we settled in to view a theatrical performance by the children of the Villa. The short play, developed over the span of nearly two months, dealt with a dream world inhabited by fantasies and nightmares. Carla, a very intelligent young girl from Casa Esperanza, played the role of the Queen of Dreamland who helped all who entered to realize their goals. After being captured by the cruel inhabitants from the Land of Nightmares, Carla was rescued by two young dreamers (Bárbara from Casa San Francisco and Jhenny from Casa Copacabana) who used laughter to conquer their fears of the nightmares. The play ended with the message that all dreams can come true through hardwork and perseverance and that no impediment, such as a nightmare, is too great to overcome.The play concluded the morning’s activities, and we all retired to the basketball court outside (luckily shaded on this sunny day) to enjoy a typical Bolivian lunch. Each visitor was treated to one of two plates, picante de pollo (spicy chicken, plantain, potato, corn, and salad) or charque (beef, potato, corn, egg, a grain called mote, and salad). As is often the case in Bolivia, the quantity of food was more than enough to satisfy one’s hunger. After finishing my plate, I excused myself to change from my Scout uniform into more formal attire for my afternoon MC duties.

The afternoon program kicked off with a cultural presentation and exposition of the works developed by the children of the Villa during the year in their classes of arts and crafts. Nine groups, representing each of the departments of Bolivia, of three to four children showed off the fruits of their labor while dancing around the gymnasium in attire typical of their represented department. The occasion served as an opportunity to orient the North American visitors to another aspect of Bolivian culture, as well as the impressive art of the Villa children.

In addition, this cultural exposition proved to be an appropriate transition to the next activity of the day: Bolivian dances. Once again, each of the nine departments were represented in a series of dances performed by children of the Villa and the boys’ and girls’ transition houses, women and their babies from Aramasi, workers and administrators of the Villa, and yes quite comically, yours truly. After the third dance, I had to relinquish the microphone to change into my indigenous garb. The dance I performed with administrators, workers, mamás and tías of the Villa is called Tinkus, which means “encounter.” It has its origins in Potosí, a mining region in southern Bolivia, and involves rival tribes who meet up several times per year to combat one another for land and women, among other things. After a month of practice once or twice per week, I felt pretty comfortable with the steps. Luckily during the performance, I did not embarrass myself additionally apart from being a clumsy gringo. In the dance, I had the dubious honor of being the winner. I say dubious, because the winner obviously receives the accolades of a champion, but it also means that you have to dance around longer than anyone else. We had never practiced in the full Tinkus attire, and by the end of the dance, I felt its weight. I was no happier than when we began to parade off stage and return to the dressing room (a.k.a. the bakery). I now have a profound respect for the traditional dancers who perform not one, but close to a dozen different dances in their shows.

In addition, this cultural exposition proved to be an appropriate transition to the next activity of the day: Bolivian dances. Once again, each of the nine departments were represented in a series of dances performed by children of the Villa and the boys’ and girls’ transition houses, women and their babies from Aramasi, workers and administrators of the Villa, and yes quite comically, yours truly. After the third dance, I had to relinquish the microphone to change into my indigenous garb. The dance I performed with administrators, workers, mamás and tías of the Villa is called Tinkus, which means “encounter.” It has its origins in Potosí, a mining region in southern Bolivia, and involves rival tribes who meet up several times per year to combat one another for land and women, among other things. After a month of practice once or twice per week, I felt pretty comfortable with the steps. Luckily during the performance, I did not embarrass myself additionally apart from being a clumsy gringo. In the dance, I had the dubious honor of being the winner. I say dubious, because the winner obviously receives the accolades of a champion, but it also means that you have to dance around longer than anyone else. We had never practiced in the full Tinkus attire, and by the end of the dance, I felt its weight. I was no happier than when we began to parade off stage and return to the dressing room (a.k.a. the bakery). I now have a profound respect for the traditional dancers who perform not one, but close to a dozen different dances in their shows. Several additional dance performances followed, and then we set up the gymnasium for the final activity of the day: the mass. The presence of three religious figures made the celebration of the mass particularly special. Reverend Ken Swanson from Christ Church Cathedral in Nashville, Father Steve Judd from the Maryknoll Language Institute in Cochabamba, and Bishop Tito Solari of Cochabamba. Together, they provided a service in Spanish and English that emphasized the ecumenical goals of the Mission and the continued cross-cultural support that helps to achieve these goals. With the participation of children, mamás and tías, administrators, and friends of the Mission, this mass was a fitting conclusion to the day’s events, as it reminded us of our spirituality, unity, and purpose in our work within Amistad.

Several additional dance performances followed, and then we set up the gymnasium for the final activity of the day: the mass. The presence of three religious figures made the celebration of the mass particularly special. Reverend Ken Swanson from Christ Church Cathedral in Nashville, Father Steve Judd from the Maryknoll Language Institute in Cochabamba, and Bishop Tito Solari of Cochabamba. Together, they provided a service in Spanish and English that emphasized the ecumenical goals of the Mission and the continued cross-cultural support that helps to achieve these goals. With the participation of children, mamás and tías, administrators, and friends of the Mission, this mass was a fitting conclusion to the day’s events, as it reminded us of our spirituality, unity, and purpose in our work within Amistad.Unfortunately, this momentous celebration could not last. With the conclusion of the mass, we had to say our goodbyes to the people of Aramasi, former workers of Amistad, and most sadly, our friends from the States. During the three days that they had been in Cochabamba, these visitors had the opportunity to see the achievements of the Mission, both in the Villa and in Aramasi. They were able to admire the continued construction of the lined, cobblestone road running through the Villa,

the lovely mural of the Virgin Mary and Jesus painted on the door of the gymnasium,

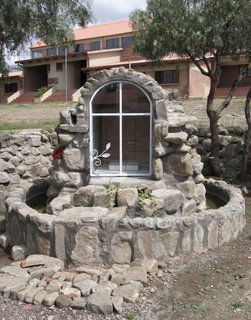

the lovely mural of the Virgin Mary and Jesus painted on the door of the gymnasium, and the beautiful grotto and fountain that honors the Virgin of Rosario (the Virgin was removed for cleaning).

and the beautiful grotto and fountain that honors the Virgin of Rosario (the Virgin was removed for cleaning). But most importantly, these visitors saw the healthy, smiling faces of the children of the Villa, who continue to grow in an environment of love and spirituality. And for me, the celebration in the Villa demonstrated that after sixteen years of service to the children of Bolivia, the Amistad Mission clearly stands as a beacon of hope for all who enter through its gates.

But most importantly, these visitors saw the healthy, smiling faces of the children of the Villa, who continue to grow in an environment of love and spirituality. And for me, the celebration in the Villa demonstrated that after sixteen years of service to the children of Bolivia, the Amistad Mission clearly stands as a beacon of hope for all who enter through its gates.

Thursday, November 30, 2006

After a couple years of relative tranquility in Cochabamba, this week the city returned to some of its old ways. On Monday, in response to a meeting of five of the nine prefects in Bolivia (each representing one of the regions here), protestors lined the streets surrounding the main plaza and expressed their disdain for the prefects´resistance to government initiatives that would require these leaders to be more fiscally responsible. While parties on both sides of the debate conveyed their beliefs in the plaza, local police gathered together to control the mob. When the tension reached its breaking point, the law enforcement officers launched tear gas to disperse the crowd. I heard from several people that it was the first time in two years that Cochabamban police had resorted to this tactic.

The restlessness exhibited Monday has carried on throughout the week. With the passage of the new law of land reappropriation (against the vehement disapproval of political parties that oppose the president) on Tuesday night, many civic groups have begun to organize their own form of protest. Tomorrow, a nationwide public transportation stoppage will be in effect. In addition, many private businesses have agreed to close their doors, in response to what they believe to be unauthorized and inappropriate use of power by Evo Morales.

If these complications were not enough already, today there is a city-wide public transportation stoppage in Cochabamba. Initiated by bus drivers, who have a surprising amount of influence in the city and who oppose the development of approximately 80 new routes throught the city (simply put, this means more competition for them), the main roads have been blocked to all traffic. Public transportation stoppages are quite the site in Cochabamba, as the usual clamour of automobiles in the streets is replaced by throngs of people walking or riding bikes. Unfortunately, this morning Pachamama decided to unleash a furious downpour on the city, making the early trek quite undesireable for those who braved the elements (myself included). Luckily, blockades in Cochabamba are not full-proof, and I was able to find a taxi trufi (collective taxi) that would take me to the center of town for three pesos (twice the normal rate, but still less than fifty cents). After weaving around the disgruntled protestors and their blockades for about twenty minutes, we finally escaped to the tranquility of the Prado. As I got out of the taxi, still soaking wet from the morning shower, I laughed at my Cochabamban adventure. Just another day in Bolivia, where nothing is certain and everything is debatable.

Saturday, November 11, 2006

As I rapidly approach the completion of my first month here in Bolivia, I thought that it might be appropriate to comment on some of the occurrences to which I have become accustomed. So, here is a list of sixteen aspects of Cochabamban life that have drawn my attention:

1. Receiving inquisitive stares from passengers while riding the public transporation system. Upon boarding a bus, I notice that many Cochabambans will fix their attention on the novelty that is the gringo. Aside from the fact that I am clearly not from Bolivia, when I choose to carry on a conversation in Spanish with a fellow passenger, especially if it concerns life in the U.S., I will surely receive many interested ears. Comically, most of the time these inquisitive listeners will act like they could care less, and then hurredly look away when we make eye contact.

2. Walking on unpaved, rock-filled roads. The vast majority of the streets in Cochabamba are unpaved, and at first it can be quite a challenge to navigate the uneven terrain. However, after continuously tredding upon these obstacles, I no longer have the constant fear of falling flat on my face. In fact, when I feel particularly bold, I will even attempt to read during my daily treks.

3. Avoiding stray dogs or carrying a rock to threaten them. The quantity of roaming canines in the city is appalling, and the probability of crossing paths with one who does not take kindly to strangers is quite high. Thus, it is best to carry at least one stone (two or three if you see a pack of dogs approaching) in hand if you suspect that you might have such an encounter. The old cliché ´´It´s not the size of the dog in the fight but the size of the fight in the dog´´ has particular relevance here. More than once, a small mutt unexpedectly has challenged my bravado, forcing me to use a warning shot (stone) to ward him off.

4. Passing by half-built buildings. Many architectural projects in Cochabamba have become victims of the economic hardship in this country. The ´´guts´´ of these structures are exposed for all to see, a sad ending to numerous well-intentioned projects that could not acquire the funds necessary to finish the job. Perhaps this dilemma also reflects notoriously poor-planning in Bolivian public projects. Frequently initiatives are begun without securing the necessary funds to see the project through to its completion.

5. Taxis honking at you even when you show no interest. If you are waiting on a street corner, whether it be to cross the road or to board one of the myriad ´´micros,´´ you can be sure that more than one taxi will honk to draw your attention. I am not sure if they believe you will be persuaded to board their autos by a persistent beeping sound, or if they merely want you to check out their uniformly-white vehicles. Either way, this act seems to be accentuated by the presence of a gringo waiting on the curb.

6. Never having the right-of-way. It is rumored that Cochabamban driving laws bestow many privileges to pedestrians, but if you assume that these mandates will be followed, you will probably pay for it. Cochabamban drivers, particularly those conducting taxis, take their dominance of the road quite seriously. You will be lucky if they halt at the absurdly few traffic lights. All of this is to say that crossing intersections in the city is an interesting game of Human Frogger (Costanza).

7. Not being able to drink the tap water. Filled with bacteria that will wreak havoc on your digestive system, the Cochabamban drinking water is not fit for outsiders. For this reason, it is always necessary to carry around a bottle of purified water, which may distinguish you as a foreigner, but is certainly more desirable than the effects brought on by invasive parasites.

8. Taking freezing cold or scalding hot showers. To be honest, it is usually a mix of both. However, there is no happy medium with the electrically-heated showerheads in Cochabamba. Finding a comfortable bathing temperature is a talent I have not yet mastered.

9. Seeing extremely-poor indigenous women with their infant children walking the same streets as businessmen in three-piece suits approaching their Ford Expeditions. The disparity between rich and poor is hugely accented in Bolivia. Whereas the middle-class in the U.S. comprises a large portion of the population, here it is almost non-existent. The vast majority of the poor in this country are indigenous, and the disdain that the privileged elite have for them is readily observable in public, both in buses and on the streets.

10. Littering. Not only is it culturally-accepted, but it is also prevalent throughout the city. The streets are covered with all kinds of plastic bags, tissues, dirty socks, wrappers, and worn shoes. You can throw just about anything in the streets (a custom I do not personally partake in), but it you happen to spit on the ground in the presence of others, you most certainly will receive dirty looks. I have not totally figured out this behavior, because, on several occasions, I have witnessed well-dressed, grown men relieving themselves on street corners. However, the scarcity of trashcans may be partly responsible for the unfortunate tendency of Cochabambinos to dispose of their waste in any convenient locatoin. In addition, there is no recycling system apart from the two-liter bottles of Coke you buy from street vendors who require an empty bottle in return for your purchase.

11. Bargaining for everything. It is not rude if done with the proper respect and is certainly necessary for a gringo. Prices for foreigners are at least twice as much, particularly when inquiring about a taxi ride. It is imperative that you and the driver agree on a price before entering the taxi, and even if, upon arriving at your destination, he (all taxi drivers are men) tells you that the distance was much greater than expected and demands a higher rate, you must be resolute and direct in your willingness to pay only the original amount.

12. The slow pace of life. For example, if you agree to meet a Bolivian at 2:00 p.m., it is probable that he or she will not arrive until 3:00 or 4:00 p.m. Tardiness is not considered rude and is extremely prevalent amongst the locals. Movies and Sunday masses are about the only social events at which punctuality is necessary. Everything else mandates a late arrival.

13. Being lost. You are lucky to find street names listed on the corners of most blocks. Those that have them are located almost exclusively in the center of town. If you want to know where you are, the best option is to ask someone who looks like they might live nearby. However, many times they will tell you it is ´´una calle innominada,`` a nameless street.

14. Walking a lot. Especially on Saturday afternoons in the center of town, it is much faster to walk than to take the uncomfortably crowded and slow ´´micros´´ (buses). If you are headed to the huge open-air market known as La Cancha during this time, you will also compete with a great deal of foot traffic. Speaking of La Cancha, this truly is the place to search for everything your heart desires. You literally can find anything you want here, from high-end electronics to llama fetuses (good luck charms when buried under the cornerstone of a newly-built house). For this reason, I now call the Internet the CyberCancha. In addition, La Cancha offers quality products for much lower prices than traditional stores. Why is this so? Nearly all of the goods are contraband in one form or another, which means that they do not come with a receipt or the option of making a return. Thus, it is absolutely necessary to test the functionality of a product before taking it with you.

15. Passing by houses with glass shards that line the outer walls. House robberies are common enough that even the most modest houses have this low-cost crime deterrent. However, after seeing quite a few abodes with this security system, I am convinced that even a mediocre thief could circumvent the sharp obstacles. Guard dogs are a different story. On several occasions, I have nearly been bitten by canines who felt that I was walking a little too close to their territory. It is best simply to run from these dogs, as they are not easily threatened by stones. Eventually, they will stop chasing you. And in the case that a dog jumps on but does not bite you in the presence of its owner, do not expect an apology. In my experience, they will blame you for getting too close.

16. Children begging for money to buy school supplies. When walking in the main plazas of Cochabamba, it is not uncommon for children dressed in shabby clothing to approach you with a list of school supplies and ask for help with the purchases. These are not scams to take advantage of sympathetic tourists. After having several conversations with such children, I have learned that some live with distant relatives hours outside of the city, go to school a couple of times per week, and have to work in the streets the rest of the time. A typical job for these young children (aroud eight-years-old) is shoe shining. They will offer you their services even if you are wearing tennis shoes. But instead of shunning their advances and continuing on my way, I have learned that it can be worthwhile to sit on a bench with them and share a small snack or Coke. They are usually quite hungry and inquisitive about life in the States.

And thus concludes a highlight of some of my experiences in Cochabamba, the breadbasket of Bolivia. With its many interesting wrinkles and personalities, this city provides lasting memories for its visitors. Life here is anything but mundane, and the possibility of the unexpected is part of the charming adventure.

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Last week, I had the opportunity to take seven of the older boys of the Villa on a rare outing in Cochabamba. The occasion was a Bolivian-produced movie called ¿Quién mató la llamita blanca? (Who Killed the White Baby Llama?). As you might imagine, the industry of Bolivian filmmaking is almost nonexistent and is comprised of a handful of directors, producers, and actors who make movies for the love of the art and not for the monetary gains reaped from their labors. Although clearly low-budget, this film provided a comedic insight into the nuances of Bolivian culture, highlighting the adventures of an indigenous couple as they traveled east from the highlands of La Paz to the lowlands of Santa Cruz. Apart from its enjoyable commentary on the idiosyncracies of the many diverse subcultures living in Bolivia, this film also addressed the exploitation and corruption of a country that historically has been marginalized by the rest of the world. All of this is to say that the film taught me a great deal about the manner in which Bolivia arrived at its current state of poverty in the third world.

However, this trip to the cinema also revealed the consciousness and gratitude of the children who accompanied me. Aside from the fact that these seven boys were elated to get the opportunity to leave the Villa for several hours and enjoy themselves in Cochabamba, they also made an effort to be respectful of the situation at hand. After we had bought the tickets for the show, we went to the concession stand to buy refreshments. When I told them that we could spend thirty bolivians (slightly less than four dollars) on whatever they wanted, Santiago, the most mature youngster in the Villa, told me that we should not spend that much. I told him that it was okay, we were having a night out and the Villa would pay for it. But he told me that we should only get a few drinks and popcorn and share them. Sure enough, the other children followed suite and insisted that we only spend half of the alloted money. Amazed at their maturity, I agreed that we would share three small cokes and two small popcorns between us and save the rest of the money. As we walked into the theater, I realized that at Santiago´s age, 13, I never would have considered such an act of humility. When we sat down in our assigned seats (such is the etiquette in Bolivian movie theaters), the children readily provided me with my own Coke and napkin full of popcorn. I told them that I wanted to share the Coke with everyone else, but they would not hear of it. Not a single child was willing to share with me. Truly, I tell you, I was wholly amazed at their generosity.

After the movie, we congregated in the lobby, and each one of the children thanked me for the experience. As in America, Bolivian movie theater lobbies are littered with videogames, and like many American children, these boys test their skills in the arcade. When they asked me if they could play for a few minutes, I told them that I did not think we had enough money (assuming that videogame prices would be comparable to those in the States, fifty cents per game). However, when they requested only one boliviano a person, I could not say no. As I doled out the seven pesos (totaling less than one dollar), these boys jumped in delight, and you would have thought that I had given them a new XBox or Playstation. Surprisingly, they were quite talented at the games they played, and those seven pesos lasted close to half an hour.

On the ride home (eight people crammed into a ridiculously small taxi), the boys continued to thank me for taking them to the theater. I told them that it was my pleasure and that I hoped to do it again soon. Who would have thought that a simple trip to the movies could bring so much joy to several young boys´lives?

Saturday, November 04, 2006

This week marked the celebration a centuries-old tradition in Bolivia, and many other parts of Latin America, known as La Fiesta de Todos Santos. Beginning at noon on November 1st and lasting until noon on November 2nd, this celebration is dedicated to the souls of the recently departed. La Fiesta de Todos Santos originated during the time of the Spanish conquest of Latin America and was used by the indigenous inhabitants as a way to combat the imposition of Spanish religion upon traditional practices. In order to honor and welcome the spirits of friends during these sacred days, family members, and other loved ones, Bolivians prepare tables of various offerings. Each offering holds a specific significance for the soul to be welcomed and usually reflects something that the departed enjoyed in life. Pictures, cigars, fruits, sweets, chicas (typical Andean beverage that may or may not contain alcohol), and plates of food are common offerings. However, no table is complete without the requisite ´´masas de pan.´´ These creations of bread from large masses of dough take many forms. The most popular is the T´antawawa, a Quechua word for bread baby. These babies represent the figure of a departed loved one and are often adorned with colorful faces. Another typical form is the ladder, which is often placed in the rear of the table and serves as a way for the soul to descend from the heavens and return upon the completion of the celebration.

In the Villa, we prepared for Todos Santos by making hundreds of T´antawawas, ladders, crosses, horses, llamas, stars, suns, etc. in our very own ´´panadería.´´

Children and mamás from all seven houses spent Tuesday afternoon molding the enormous quantity of dough into all kinds of creative forms. I tried my hand at this surprisingly difficult task (six-year-old children were putting my moldings to shame, compare our work in the photos)

Children and mamás from all seven houses spent Tuesday afternoon molding the enormous quantity of dough into all kinds of creative forms. I tried my hand at this surprisingly difficult task (six-year-old children were putting my moldings to shame, compare our work in the photos)

and managed to form several resemblences of stars, suns, moons, and hearts. All together, this project took around twelve hours, and when I retired from my labor after dinner and went to relax in my room, I could still hear the mamás working diligently (until around midnight).

and managed to form several resemblences of stars, suns, moons, and hearts. All together, this project took around twelve hours, and when I retired from my labor after dinner and went to relax in my room, I could still hear the mamás working diligently (until around midnight). Although I would find out the next day that most of my forms had either burned or come detached while in the oven, I was encouraged by the dedication and reflection of both the children and mamás during this sacred celebration. In the process of making the bread figures, I heard children and mamás talking about who a specific T´antawawa represented and what that person enjoyed doing in life. For me, La Fiesta de Todos Santos was a welcome alternative to the American tradition of Halloween. In place of Halloween´s bestowal of pounds of candy to costumed children, Todos Santos gives family members and friends the opportunity to honor the memory of loved ones. In the States, I have encountered few celebrations that have the level of thoughtfulness and preparation that can be found in Todos Santos in Bolivia.

That being said, I will digress for a minute from this fascinating tradition to discuss the unfortunate influence of our American celebration of Halloween on Bolivian culture. In the past few years, as I am told, Halloween has become increasingly popular amongst the Bolivian middle and upper classes. In an attempt to separate themselves from the archaic and ridiculous custom of Todos Santos, these privileged elite adorn their children in elaborate costumes (the disguise from the movie ´´Scream´´ is quite popular) and convene in a central location. That location in Cochabamba just so happens to be in the center of the city in an icon of American influence: Burger King. As I passed by the BK on Tuesday afternoon, I was astonished to see the mass of children pouring out of the entrance and running around to the drive-thru to play games with a clown who was calling out trivia from a microphone (´´What color is the sky? You`re right, it´s blue. Here´s a piece of candy.´´) I couldn´t help but feel sorry for these children, who would probably never partake in the symbolic tradition of their own country. Like many of us, they probably believe that the last day in October is an excuse to fill their stomachs with chocolates.

Returning briefly to the tradition of Todos Santos, the celebration concludes on November 2nd at noon, a time at which many Cochabambinos can be found at the only public cemetary. It is customary to go and place flowers in front of the tombstones (which are stacked on top of one another, grass plots are only found in private cemetaries) of loved ones who have died in the past year. After the first year, most families stay at home and pray over the offerings they have brought to the table. Also at this time, neighbors and friends are invited to the house to take an offering from the table and pray for one of the departed. In this manner, all of the offerings are eventually taken from the table and consumed. The souls of the departed are then ushered back to the heavens until the following year. Interestingly, this act sometimes involves costumed ´´spirits´´ that are gingerly beaten by indigenous Quechua women. And thus concludes the ceremony of Todos Santos, a lasting reminder of our interconnectedness with the spirits of the deceased.

Saturday, October 28, 2006

One of the biggest concerns that I have for the children who live in the Villa is the enclosure of the Villa itself. Surrounded on all sides by barbed wire fences, you get the feeling that you are trapped inside. Even after two weeks, I have experienced moments in which it seemed that I was in a prison rather than a loving orphanage. The fortified surroundings of the Villa are by no means intended to create such emotions. To the contrary, they keep the many young children safe from dangerous intruders and the numerous stray dogs that prowl the neighborhood. But on more than one occasion, I have talked to mamás who say the children in their house are bored of the routine of going to school and coming back to the Villa for the rest of the day. These children, they tell me, probably know fewer parts of Cochabamba than I do. They also attribute some of the children´s aggressive behavior to the fact that they are isolated most of the day. Whenever I leave the Villa to walk up the road and catch the bus, I have several children ask me if they can accompany me. When I tell them that I am only going a few blocks, they say that they don´t care, that they just want to tag along.

I worry that these children´s intellectual and cultural growth is being impeded by the enclosure of the Villa. When the children do not get the opportunity to go into the city and interact with others outside the Villa, it compounds their feelings of isolation that stem from being abandoned. During my first two days here, in which I partook in meetings between the mamás, tiás, and administration, I heard many plans to have more outings in the upcoming year. I hope that this will be the case, but as progress and change is notoriously slow in Bolivia, I would prefer not to wait and see if these ideas come to fruition. As part of my schedule, I want to start taking the older children out on Friday nights to see more of the city. Whether it be going to a movie, taking in a play, or watching a sporting event, I am convinced that these children need more social contact. There is no activities coordinator in the Villa, and so usually on weekend nights, children go to the gym and play until they are tired (which doesn´t happen before 11). I have started to encourage the mamás to have their children accompany them when they run simple errands, and I think that many of them are already doing so. Hopefully, short trips to places outside the neighborhood will become commonplace.

In the Villa, Tuesday nights before dinner are reserved for dance classes. Estela, the instructor, usually comes to teach a variety of traditional dances to a crowd of about thirty children. This past Tuesday, however, was an exception, as the mamás and tías were the ones in the limelight. In anticipation of the 17th anniversary party of the Villa in December, Estela has begun training the adults in the Villa folkloric dances. I knew nothing of this until Evelyn, a young girl from La Casa Kantuta, knocked on my door at 6 on Tuesday night and told me that the dance classes were about to start. I asked her what she was talking about, and she reminded me of how I had agreed to dance in the fiesta in December. I certainly did not remember saying anything of the sort, but I also did not want to disappoint the many children (apparently) who were waiting outside the gym to see me perform. As I entered the gym, some of the excited children clapped their hands, while others led me to the center of the group of mamás and tías. I sheepishly said hello and immediately felt awkward upon noticing that I was the only male in the group. I asked if these dance lessons were for women only, but Estela assured me that men were an important part of the dance we were going to practice called ´´Tinku.´´ Yes, men, I thought, not just one American who has no clue what he is doing.

Still not feeling wholly comfortable but realizing that I was not going to be able to escape easily, I tried to prepare myself for the lesson. Estela said that we were going to do some exercises before we got started, which I interpreted as stretching to warm up the muscles before some serious cardio. It turns out that she meant we were going to get to know each other´s body chemistry better by pairing off and mimicking our partner´s movements. While it seemed comical and mundane, it did help me to focus on what we were doing. After several more similar exercises, we lined up for the real deal. I was sure that I would be lost amongst these people who had grown up watching the popular Tinku dance. But my worries were quickly eased when Estela showed me the one movement that the men perform--an upward thrust of the right knee and some bouncing from side to side. Even a gringo with two left feet like me could master this part. I danced in front of the women, bobbing up and down, leading them to the end of the basketball court. Outside of the gym, the children peered in and cheered me on (or they mocked my style, not really sure). In any event, after an hour of this repetitive motion my right leg ached, and I was sure that the nightime games of basketball and soccer were going to be difficult. Finally, Estela called for us to stop, and I issued a sigh of relief. Despite the fact that I was tired and in need of a Bengay treatment, I was happy that I had gone and learned the dance. As the mamás and tías filed out of the gym, I asked Estela if she could bring me a video of the dance next week, so that I could see what it really looked like in action. She agreed and thanked me for my enthusiasm. More importantly, she promised me that I would not be the only male in the dance during the big fiesta.

When I left the gym, the children who had watched the lesson complimented me on my form and energy (which may have been a little too much, as Bolivians are pretty reserved people). Even though I thought I had probably looked quite silly during the dance, I appreciated their support. I got the opportunity to actively participate in a part of the Bolivian culture that I otherwise would never have pursued. I hope that by next Tuesday I will have improved and that I will have a male counterpart to share in the experience.

Sunday, October 22, 2006

After one week living in the Villa and getting to know all of the children, mamas, and tías, I am becoming acclimated to the daily routine. After morning spiritual reflection and prayer, the children who go to school in the afternoon stay in the Villa and perform chores, such as watering the many plants in the Villa, cleaning their respective houses, and washing their clothes. Other children attend various workshops, such as musical training, arts and crafts, and academic tutoring. Mornings are relatively peaceful and afford me the opportunity to interact with the children on an individual basis.

Thursday morning I relived my days as a young child by playing in the sandbox with five of the young children who were on a break from their Montessori classes in the Villa. I was surprised by how much I actually enjoyed building sandcastles and waterways to sculpted docks and pools. The children were particularly thrilled when we dug holes in all four corners of the sandbox and formed passageways leading to a large cavern in the center. They jumped up and down clapping as they filled the holes with water and saw the slow streams creaping towards the middle of the sandbox. Within several minutes we had most of the sandbox flooded, and the children began splashing each other with water.

While playing in a sandbox seems to be nothing more than a juvenile activity, it highlights something that I have noticed in my first week here; that is, these children receive great joy from simple things. Whether it is getting a piggy-back ride, singing songs, or jumping rope, the children of the Villa are happy to be outside and engaged in any activity. Instead of playing videogames (which they don´t have) or chatting on the Internet (which they do have), they prefer to partake in games with each other.

Friday afternoon, Zulma, the mama of La Casa San Francisco asked me to walk with her to take two of her boys to school. She told me that they ha been having a lot of difficulty recently, wanting to leave the Villa to live with their biological Mom in Santa Cruz. Zulma said that one of the brothers was leaving school midway through class and wandering around the neighborhood outside the Villa. They did not want to do homework and were not stimulated by any of the activities offered in the Villa. On our walk back to the Villa, Zulma asked me if I would talk to them and try to help. I agreed, and the last two days I have tried to slowly develop a closer relationship with the boys. The type of emotional burdens that these boys carry surely are not to be resolved quickly or easily, but I was encouraged this morning when I sat next to one of the boys in church and he put his arm around me and told me he was glad that I was there. Because the boys of the Villa have a lot fewer interactions with men than women, I hope that my presence will be a positive change for them. Basketball practices will start this week, and many of the older boys in the Villa have showed interest. Sports seem to be a great way to communicate with them, and I am hopeful that these practices will be a bonding experience for everyone.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

After spending two relaxing weeks in Buenos Aires, Argentina with my friend Sam (who has a delicious burrito restaurant in the center of the city, www.californiaburritoco.com), I arrived in Cochabamba, Bolivia. Although it had been three years since I last came to Cochabamba, everything seemed to be quite familiar. From the incredibly lax immigration checkpoint to the inevitable bartering with taxi drivers, and of course the imposing statue of Cristo de la Concordia, I felt as if I had not been away from Cochabamba for more than a few months.

However, my excitement upon seeing familiar landmarks was secondary to the anticipation I had to see the children of the Villa. Alas, upon arriving that first day, most of the children were at school and a major planning project was underway in a nearby residence of the Villa called La Morada. At La Morada, I met and reunited with the mamas of the Villa, who were discussing activities and goals for the upcoming year. These discussions would last two days, and during this time, I learned a great deal about the daily operations of the Villa, as well as the difficult emotional circumstances in which these children are living. One of the administrators at the Villa noted that 70% of the children do not know the facts of their origin. And as many of the mamas noted in our discussions, one of the greatest challenges they face is explaining to a child that he or she was abandoned. When I asked individual mamas how they dealt with this situation, I received different answers, some preferring to be direct and telling the child that their parents could not support them and others opting to say that their mother or father was working so that one day they could be reunited with their child. I do not feel that I am in any place to judge whether one approach is better than the other, and through these conversations, I began to develop a great respect for the mamas of the Villa and the courage and dedication they impart to each child under their care.