With the summer vacation coming to a close, the mamás of the Villa decided to give the children an uncommon treat: an adventure to the highest city in the world. After several weeks of planning and several days of waiting for roadblocks and violence to end in Cochabamba, a trip to Potosí was finally achieved. Leaving on a Monday night around 10 o’clock (in typical Bolivian fashion, the bus we commissioned arrived two hours late), fifty-two eager children, seven mamás, Gualberto, and an awkward gringo packed into a “flota” designed for thirty-six passengers. Upon loading numerous blankets and gigantic suitcases in the storage compartments below, we crammed ourselves into the overwhelmed vehicle. In order to make space for everyone, mattresses were laid in the aisle, and the littlest children sprawled out in the last remaining empty spaces. Despite the ridiculously crowded conditions (three people to every two seats), the children remained quite animated. We spent the first hour of the bus ride singing spiritual songs (of which the children know dozens) and laughing at our contortioned bodies struggling to find a comfortable seated position.

Unfortunately, the road to Potosí is neither short nor straight. After about the fourth hour of the fourteen-hour journey along endless windy roads to an altitude of 4300 meters, the children grew restless. Without a bathroom in the bus and no convenient or safe place to stop in the middle of the night with numerous young children, the ride became a test of attrition. Instead of sleeping comfortably on their mattresses, the young children cried out in hunger and pain. Daybreak could not have come sooner, and when we finally stopped at a small village (still about seven hours from Potosí), the children made a dash to the bathrooms. After “filling” ourselves with tea and a piece of bread with butter, we headed back to the mobile prison that awaited us. Luckily, a sleepless night and a bit of nourishment proved to be enough to put most of the children into a peaceful slumber.

At noon, we arrived at the bus terminal in Potosí and waited for Gualberto to get transportation to our hostel. But our wait was in vain, as Gualberto returned to tell us that our reservations had been given away to another group. Oh, Bolivia. So we spent another two hours in the bus terminal trying to arrange other lodging (no small feat for sixty people).

Gualberto was able to eventually get us a place in a retreat area for church groups about twenty kilometers outside of the city. We then packed all of our stuff into three vans and backtracked for thirty minutes. Upon arriving at the church, the children were less than pleased and began to argue about who would sleep in each room (the altitude and fatigue were not helping the cause). But we were able to get everyone to settle down and eat a late afternoon soup in the mess hall. After our “early-bird special,” Gualberto told the children that we were going to turn in for the night. As it was five o’clock in the afternoon, I thought that he might be joking. However, he was not, and the children did not put up much of a fuss about sleeping when three hours of daylight (i.e. playtime) remained.

Gualberto was able to eventually get us a place in a retreat area for church groups about twenty kilometers outside of the city. We then packed all of our stuff into three vans and backtracked for thirty minutes. Upon arriving at the church, the children were less than pleased and began to argue about who would sleep in each room (the altitude and fatigue were not helping the cause). But we were able to get everyone to settle down and eat a late afternoon soup in the mess hall. After our “early-bird special,” Gualberto told the children that we were going to turn in for the night. As it was five o’clock in the afternoon, I thought that he might be joking. However, he was not, and the children did not put up much of a fuss about sleeping when three hours of daylight (i.e. playtime) remained. I followed nine boys up the stairs to our room and climbed into my bottom bunk bed. The boys were willing to put on their pajamas and brush their teeth, but once they had settled into bed, typical boy behavior took over. This was one of the few independent sleepovers that they had ever had, and the teasing and shenanigans ensued for about two hours. I did not want to deprive them of their fun, but when girls from the next room came to complain of the rowdiness, I had to calm them down…or at least try. They were quiet long enough for me to fall asleep, but apparently not enough so to satisfy the mamás and tías in the adjacent rooms. I am told that on two occasions one of them came in to chastise the boys. However, it’s all hearsay to me, because few things could have disturbed me after the previous twenty-four hours.

In the morning, I awoke to the elated shouts of the boys repeating, “Vamos a las aguas termales!” Forget about the hundreds of years of rich history in Potosí, a day at the hot springs had been promised to the children and for them that was the most anticipated adventure in our trip. While the location of the hostel was inconvenient for exploring the city of Potosí, it was perfect for our day at the hot springs. We took an easy fifteen-minute walk along the road and arrived at a recreational complex. The hot springs were not the bubbling pools surrounded by lush vegetation that I had expected. Rather, the “hot springs” consisted of one large swimming pool with an enormous tarp shading it (the power of the Potosian sun is not to be taken lightly). I personally was not too thrilled about the pool, but the children did not hesitate to leap in with joy.

However, after surfacing, all but a few children quickly scrambled to the side of the pool. I realized that they did not know how to swim. I was not alone, though, and another adult in the pool tried to teach them. After several frustrating attempts and fearful screams, the children pretty much gave up on learning. Even so, they still enjoyed throwing balls to each other and inventing different water games.

However, after surfacing, all but a few children quickly scrambled to the side of the pool. I realized that they did not know how to swim. I was not alone, though, and another adult in the pool tried to teach them. After several frustrating attempts and fearful screams, the children pretty much gave up on learning. Even so, they still enjoyed throwing balls to each other and inventing different water games. After a full day at the pool, it was time to go back to our hostel for another early dinner. The children ate quickly, and then we went to play tag in the courtyard. After an hour or so, Gualberto told us that it was time to get ready for bed. It was only seven o’clock, but we were going to get an early start in the morning to visit the old coin mint and the famous mines of Potosí. Luckily, the boys in my room were much calmer this night and did not protest when the lights went out at eight.

The trip to the coin mint was well worth the six o’clock wakeup. Built during the time of Spanish rule in Bolivia, it provided enormous wealth to the conquistadors who exploited the immense silver deposits in the hills of Potosí. In the seventeenth century, Potosí was one of the largest and richest cities in the world.

This wealth came at the cost of many African and indigenous slaves, who were used to extract silver from Cerro Rico and make it into coins and jewels. The coin mint that we visited revealed part of this tragic story. Heavy cranks, wheels, and other machinery were lasting reminders of the countless deaths suffered by the slaves who toiled under the supervision of Spanish overseers. Once a mold was made, each coin was individually stamped with the use of a sledgehammer. It is estimated that millions of coins were made in this one site.

This wealth came at the cost of many African and indigenous slaves, who were used to extract silver from Cerro Rico and make it into coins and jewels. The coin mint that we visited revealed part of this tragic story. Heavy cranks, wheels, and other machinery were lasting reminders of the countless deaths suffered by the slaves who toiled under the supervision of Spanish overseers. Once a mold was made, each coin was individually stamped with the use of a sledgehammer. It is estimated that millions of coins were made in this one site.Although the coin mint was the dreadful house for the production of Spanish silver for many years, the true sorrow of Potosí is found in the mines of Cerro Rico.

For the last 450 years, these mines have been bled of almost all their profitable minerals. Some estimates say that over eight million people have died over this time. Apart from the danger of falling rocks and dynamite explosions, the prevalence of silicosis, a pulmonary disease that eventually causes the lungs to burst, amongst those who work in the mines provides an additional threat. It is hard to imagine how awful these conditions truly are, but we were able to see a glimpse of this depressing life on a guided tour of the mines.

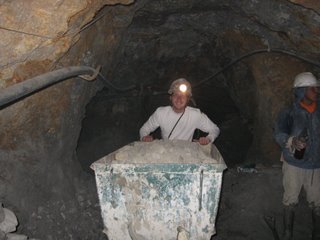

For the last 450 years, these mines have been bled of almost all their profitable minerals. Some estimates say that over eight million people have died over this time. Apart from the danger of falling rocks and dynamite explosions, the prevalence of silicosis, a pulmonary disease that eventually causes the lungs to burst, amongst those who work in the mines provides an additional threat. It is hard to imagine how awful these conditions truly are, but we were able to see a glimpse of this depressing life on a guided tour of the mines. Gualberto, four mamas, twelve children, and I took a ride up to Cerro Rico in the afternoon to visit the mines. Upon arriving at the base, we bought coca leaves, alcohol, cigarettes, and dynamite (it doesn’t look like the sticks you see in the movies) to give to the miners who often work twelve to fifteen hours a day. We then proceeded up the hill and found two miners who would guide us through the confusing labyrinth. It is not permitted to go without a guide, and for good reason. Once we were inside, it was as if we had entered another world, full of winding tunnels, tracks, and piles of rock. One of our guides told us that it was appropriate to give gifts to every group of miners who we talked to. The first group we encountered were mere boys, probably no older than sixteen. Shy at first, they came shooting out of their holes when we told them that we had soft drinks to share. The way that they gulped down these refreshments would make you think that we had given them something much more precious.

At the next station, about two hundred meters inside the mine, we came to a group of men who were banging away at a sheet of rock. Here we offered them dynamite, coca leaves, and cigarettes. They were happy to receive them, but were hoping for a bottle of alcohol. We told them that all we had were small bottles of rubbing alcohol to offer to El Tío.

Speaking of El Tío, it is worth explaining a little bit about the important role of this deity. El Tío is the miners’ representation of the devil and is thought to be the power that controls the fortune of the miners.

In every mine of Cerro Rico there is a statue of El Tío, and miners come daily to give offerings to him. Whether it be coca leaves, alcohol, or cigarettes, the miners believe that if they do not pay homage to El Tío, they will extract few minerals and may even die in an accident. When we visited El Tío, the mamás (some of whose parents had worked in the mines) were adamant about being respectful to him. In turn, we presented our offerings to El Tío and reflected in silence for several minutes. I then asked to take one of the mama’s pictures with El Tío, and she told me absolutely not. You may take a picture of him alone, but never with anyone else. Regardless of my own beliefs, I certainly did not want to offend traditional practices.

In every mine of Cerro Rico there is a statue of El Tío, and miners come daily to give offerings to him. Whether it be coca leaves, alcohol, or cigarettes, the miners believe that if they do not pay homage to El Tío, they will extract few minerals and may even die in an accident. When we visited El Tío, the mamás (some of whose parents had worked in the mines) were adamant about being respectful to him. In turn, we presented our offerings to El Tío and reflected in silence for several minutes. I then asked to take one of the mama’s pictures with El Tío, and she told me absolutely not. You may take a picture of him alone, but never with anyone else. Regardless of my own beliefs, I certainly did not want to offend traditional practices.

We spent another half-hour in the mines and then got escorted out of the muddy tunnels by our guides. On the way back, I stayed in the back with one of the guides and asked him about life in Cerro Rico. He, twenty-one years old, told me that he had been working for seven years in the mines and made about five dollars per day. Today, almost all of the silver has been extracted from the mines, and only in the deepest, most dangerous parts can you find small deposits. Other less valuable minerals and metals, such as tin, are now the principle extractions from the mines. In the hour and a half that we were in the mines, the heartbreaking existence of those who work there overwhelmed me. The tools and techniques that the miners use today have not changed much from a century ago, and the faces of these workers reveal the rigor of their labor.

We spent another half-hour in the mines and then got escorted out of the muddy tunnels by our guides. On the way back, I stayed in the back with one of the guides and asked him about life in Cerro Rico. He, twenty-one years old, told me that he had been working for seven years in the mines and made about five dollars per day. Today, almost all of the silver has been extracted from the mines, and only in the deepest, most dangerous parts can you find small deposits. Other less valuable minerals and metals, such as tin, are now the principle extractions from the mines. In the hour and a half that we were in the mines, the heartbreaking existence of those who work there overwhelmed me. The tools and techniques that the miners use today have not changed much from a century ago, and the faces of these workers reveal the rigor of their labor. Although I can attempt to describe my brief experience in the mines, I would encourage anyone interested in learning more about Cerro Rico to watch a documentary called “The Devil’s Miner.” You can get it at Blockbuster or on NetFlix, and it is incredibly powerful. After our trip, I showed it to the children in the Villa, and I think that some of them became very appreciative of the life and support that they have at Amistad.

Although I can attempt to describe my brief experience in the mines, I would encourage anyone interested in learning more about Cerro Rico to watch a documentary called “The Devil’s Miner.” You can get it at Blockbuster or on NetFlix, and it is incredibly powerful. After our trip, I showed it to the children in the Villa, and I think that some of them became very appreciative of the life and support that they have at Amistad. The visit to Cerro Rico was a moving and fitting conclusion to our trip to Potosí. The bus ride back to Cochabamba was much more comfortable, as we took a flota with fifty-seats. Interestingly, this larger bus only took nine hours to get back to the Villa. And upon arriving at five in the morning, we were all ready for a long nap. A journey to the highest city in the world can be quite exhausting.

<< Home