Classes began this past week, and with the start of a new scholastic year, certain expectations have been put on the children in the Villa. Last year a number of students failed their grade and will be repeating the same classes. In order to avoid a similar occurrence, the administration and mamás have decided to remove the televisions from the six houses that had them, demand a regular study period, and require perfect attendance (except in cases of illness). One result of this exigency has been a large increase in the number of children who come to the Reading Room. In the morning, as many as twelve children at once are in the Room reading or asking to borrow books. This week I am planning to start a program that rewards the children for their interest in the written word. Each time that they complete a book, they will be able to put their name and the book they read in a list. After a certain number of books, they will receive small prizes. I remember Book It from my childhood and how I used to love eating personal pan pizzas at Pizza Hut as a reward. What is most encouraging to me is that the children come and ask me to read at all hours of the day. Regardless if I am in the middle of basketball practice or individual time in a house, the children often will plea with me to give them the key to the Reading Room. I tell them to ask Daisy for the key, but they insist on using mine. Although the children are generally very respectful of the rules in the Reading Room, it is still necessary to have someone in charge of checking-out and returning books. For now, the only problem is having someone for this purpose in the Reading Room at all hours of the day. The children have two hours in the morning with me and two hours in the afternoon with Gray, but there are three hours in the late afternoon in which the Room is closed. This week, I hope to find someone in the Villa who will be able to help out during this time, so that a desire to read will continue to grow in the children.

Wednesday, February 21, 2007

A week ago, a group of six leaders from the Villa’s Scouts program, Sonia, Rosi, Claudia, Pamela, Tatiana, and I, met early Sunday morning in a nearby suburb of Cochabamba. In our weekly leaders’ meeting, Sonia had told us about a project that she had been working with for the past year in Quillacollo that gives support to street children in the area. One of the biggest problems in starting programs like these to help such children, she said, was that public officials do not know how many or in what areas these children live. She asked for our help in taking a census of these children to determine where aid could best be utilized.

So, at seven on Sunday morning, I boarded a bus with Claudia to take the hour trip to Quillacollo. During the journey, Claudia and I practiced the questions that we were to ask “street children” between five and eighteen years old. Even after we arrived in Plaza Bolívar and were briefed on how to identify and interview the children, I had my doubts about who was a proper candidate to solicit. Sonia told me not to worry and to use my best judgment.

We then divided up into small groups and headed toward different sections of Quillacollo. With my twenty-two interviews and coupons (for the children to receive free bananas and milk in the main plaza), I headed toward the central marketplace. When we arrived, Claudia, Pamela, and I split up and agreed to meet back in four hours. I began scanning the area for prospective interviewees and quickly located a young girl selling fruit on the side of the street. I approached her, introduced myself, explained what I was doing, and asked if she would participate. At first she seemed confused and hesitant, even after I told her that she could get free bananas and milk. But when I told her that I also had some gum for all those who helped out, she immediately agreed. I admit, my method may have been a little coercive, but hopefully the anonymous information that she provided me with outweighs any adverse affects she may have felt.

We began the interview, and she told me that she was seven years old and helped her mother in the market on weekends. When I asked her where her mother was, she just waved in a general direction. Her three younger brothers were playing nearby in the plaza but without adult supervision. The interview sheet required me to ask some personal questions about her family, such as if she had experienced physical abuse at home. However, I did not feel comfortable posing such questions to a child who I had just met, and so for the rest of the day I avoided the more invasive interrogatories. I thought if the goal of the census was to identify the quantity and location of street and troubled children, the mere fact that a seven-year-old girl was alone and selling fruit in the street was enough information to qualify her as someone who needed aid. I completed the interview by talking about school and her favorite subjects and giving her the food coupon and gum. She seemed very pleased to receive both and even more excited when I told her that the gum was from the United States. I thanked her for her time and wished her well in her vending.

Glad to have the first interview out of the way and without any problems, I continued searching for more young children. I found three brothers playing on a curb nearby and asked if they wanted to participate. In unison, they replied, “Sí, sí, yo primero.” We finally agreed that we would go in chronological order of age, starting with the youngest. After the first interview, in which the six-year-old boy told me that he sold vegetables in the street on Sundays with his brothers, the next two were straightforward. The oldest brother (10) mentioned that their father had abandoned the family when he was five, and that their mother and grandmother cared for them. The regrettable circumstance of one-parent households is an all too common reality in Bolivia, and as the children talked about the absence of a father in their own lives, they did so as if it were nothing out of the ordinary. Once again, I tried to end the interview with a short chat about something light. The boys mentioned Spider Man, so I rolled with it and talked about villains and friends of the superhero. The youngest insisted on acting out Spider Man’s web slinging attacks, and we all had a laugh when he fell into a pile of papayas. I gave the children the compensation for the interview and told them to keep practicing their Spider Man moves.

Four down and feeling good about my quick progression, I continued around the market square and encountered a ten-year-old girl selling peaches and oranges. In between sells, she agreed to the interview, and we started with some basic questions. But about half-way through the interview, a man to her right starting asking me questions about when and how the children of Quillacollo would receive benefits from this project. I told him that I honestly did not know but that it was first necessary to have an idea of how many and what kind of children lived in need. Not impressed with the offer of bananas and milk in the central plaza, he said that I needed to leave. I asked him, “Why, are you her father?” He replied, “Yes, and I would like you to leave now.” So I asked the girl, “Is this your father?” She told me yes, and I walked away. Perhaps it was the fact that I am a gringo, or more exactly, with my interviewer badge, glasses, and pale skin I looked like one of the many Mormon converters in Cochabamba. Regardless, the information from this interview was destined for the trashcan.

Luckily, I did not have any more experiences as confrontational as this one. Four or five indigenous women refused my offers for interviews with their children, but I had expected to get rejected more times than I did. In addition, I had some interesting encounters. I interviewed a Quechua woman and her six-year-old son, me only speaking Spanish to her and her only speaking Quechua to me. Although I know the whole of two words in this native tongue, I was able to conduct a fairly comprehensible interview through gestures and support from the child. In another situation, I walked five blocks with a nine-year-old boy pushing a loaded cart while asking him questions about his family life. In yet another instance, I went to a videogame arcade and conducted two interviews with boys who were battling each other in Mortal Kombat. In between shouts of victory and defeat, I found out that they sell ice cream on the streets on the weekends and share a small room with their two younger brothers. But they were clearly more interested in exacting Fatalities on one another than in the interview.

After nearly five hours of talking to a variety of children, youths, and parents, I was exhausted. I met up with the rest of the Scout group in the central plaza, and we shared our experiences. Together, we had accomplished more than 120 interviews and encountered many different personalities. Compiled with the help of other groups of volunteers, we had achieved more than 500 interviews. When and how the needy children of Quillacollo will be helped, I do not know. But on the bus ride back to the center of Cochabamba, I felt that I had at least contributed to the process that would eventually result in better lives for these children.

Wednesday, February 07, 2007

With the summer vacation coming to a close, the mamás of the Villa decided to give the children an uncommon treat: an adventure to the highest city in the world. After several weeks of planning and several days of waiting for roadblocks and violence to end in Cochabamba, a trip to Potosí was finally achieved. Leaving on a Monday night around 10 o’clock (in typical Bolivian fashion, the bus we commissioned arrived two hours late), fifty-two eager children, seven mamás, Gualberto, and an awkward gringo packed into a “flota” designed for thirty-six passengers. Upon loading numerous blankets and gigantic suitcases in the storage compartments below, we crammed ourselves into the overwhelmed vehicle. In order to make space for everyone, mattresses were laid in the aisle, and the littlest children sprawled out in the last remaining empty spaces. Despite the ridiculously crowded conditions (three people to every two seats), the children remained quite animated. We spent the first hour of the bus ride singing spiritual songs (of which the children know dozens) and laughing at our contortioned bodies struggling to find a comfortable seated position.

Unfortunately, the road to Potosí is neither short nor straight. After about the fourth hour of the fourteen-hour journey along endless windy roads to an altitude of 4300 meters, the children grew restless. Without a bathroom in the bus and no convenient or safe place to stop in the middle of the night with numerous young children, the ride became a test of attrition. Instead of sleeping comfortably on their mattresses, the young children cried out in hunger and pain. Daybreak could not have come sooner, and when we finally stopped at a small village (still about seven hours from Potosí), the children made a dash to the bathrooms. After “filling” ourselves with tea and a piece of bread with butter, we headed back to the mobile prison that awaited us. Luckily, a sleepless night and a bit of nourishment proved to be enough to put most of the children into a peaceful slumber.

At noon, we arrived at the bus terminal in Potosí and waited for Gualberto to get transportation to our hostel. But our wait was in vain, as Gualberto returned to tell us that our reservations had been given away to another group. Oh, Bolivia. So we spent another two hours in the bus terminal trying to arrange other lodging (no small feat for sixty people).

Gualberto was able to eventually get us a place in a retreat area for church groups about twenty kilometers outside of the city. We then packed all of our stuff into three vans and backtracked for thirty minutes. Upon arriving at the church, the children were less than pleased and began to argue about who would sleep in each room (the altitude and fatigue were not helping the cause). But we were able to get everyone to settle down and eat a late afternoon soup in the mess hall. After our “early-bird special,” Gualberto told the children that we were going to turn in for the night. As it was five o’clock in the afternoon, I thought that he might be joking. However, he was not, and the children did not put up much of a fuss about sleeping when three hours of daylight (i.e. playtime) remained.

Gualberto was able to eventually get us a place in a retreat area for church groups about twenty kilometers outside of the city. We then packed all of our stuff into three vans and backtracked for thirty minutes. Upon arriving at the church, the children were less than pleased and began to argue about who would sleep in each room (the altitude and fatigue were not helping the cause). But we were able to get everyone to settle down and eat a late afternoon soup in the mess hall. After our “early-bird special,” Gualberto told the children that we were going to turn in for the night. As it was five o’clock in the afternoon, I thought that he might be joking. However, he was not, and the children did not put up much of a fuss about sleeping when three hours of daylight (i.e. playtime) remained. I followed nine boys up the stairs to our room and climbed into my bottom bunk bed. The boys were willing to put on their pajamas and brush their teeth, but once they had settled into bed, typical boy behavior took over. This was one of the few independent sleepovers that they had ever had, and the teasing and shenanigans ensued for about two hours. I did not want to deprive them of their fun, but when girls from the next room came to complain of the rowdiness, I had to calm them down…or at least try. They were quiet long enough for me to fall asleep, but apparently not enough so to satisfy the mamás and tías in the adjacent rooms. I am told that on two occasions one of them came in to chastise the boys. However, it’s all hearsay to me, because few things could have disturbed me after the previous twenty-four hours.

In the morning, I awoke to the elated shouts of the boys repeating, “Vamos a las aguas termales!” Forget about the hundreds of years of rich history in Potosí, a day at the hot springs had been promised to the children and for them that was the most anticipated adventure in our trip. While the location of the hostel was inconvenient for exploring the city of Potosí, it was perfect for our day at the hot springs. We took an easy fifteen-minute walk along the road and arrived at a recreational complex. The hot springs were not the bubbling pools surrounded by lush vegetation that I had expected. Rather, the “hot springs” consisted of one large swimming pool with an enormous tarp shading it (the power of the Potosian sun is not to be taken lightly). I personally was not too thrilled about the pool, but the children did not hesitate to leap in with joy.

However, after surfacing, all but a few children quickly scrambled to the side of the pool. I realized that they did not know how to swim. I was not alone, though, and another adult in the pool tried to teach them. After several frustrating attempts and fearful screams, the children pretty much gave up on learning. Even so, they still enjoyed throwing balls to each other and inventing different water games.

However, after surfacing, all but a few children quickly scrambled to the side of the pool. I realized that they did not know how to swim. I was not alone, though, and another adult in the pool tried to teach them. After several frustrating attempts and fearful screams, the children pretty much gave up on learning. Even so, they still enjoyed throwing balls to each other and inventing different water games. After a full day at the pool, it was time to go back to our hostel for another early dinner. The children ate quickly, and then we went to play tag in the courtyard. After an hour or so, Gualberto told us that it was time to get ready for bed. It was only seven o’clock, but we were going to get an early start in the morning to visit the old coin mint and the famous mines of Potosí. Luckily, the boys in my room were much calmer this night and did not protest when the lights went out at eight.

The trip to the coin mint was well worth the six o’clock wakeup. Built during the time of Spanish rule in Bolivia, it provided enormous wealth to the conquistadors who exploited the immense silver deposits in the hills of Potosí. In the seventeenth century, Potosí was one of the largest and richest cities in the world.

This wealth came at the cost of many African and indigenous slaves, who were used to extract silver from Cerro Rico and make it into coins and jewels. The coin mint that we visited revealed part of this tragic story. Heavy cranks, wheels, and other machinery were lasting reminders of the countless deaths suffered by the slaves who toiled under the supervision of Spanish overseers. Once a mold was made, each coin was individually stamped with the use of a sledgehammer. It is estimated that millions of coins were made in this one site.

This wealth came at the cost of many African and indigenous slaves, who were used to extract silver from Cerro Rico and make it into coins and jewels. The coin mint that we visited revealed part of this tragic story. Heavy cranks, wheels, and other machinery were lasting reminders of the countless deaths suffered by the slaves who toiled under the supervision of Spanish overseers. Once a mold was made, each coin was individually stamped with the use of a sledgehammer. It is estimated that millions of coins were made in this one site.Although the coin mint was the dreadful house for the production of Spanish silver for many years, the true sorrow of Potosí is found in the mines of Cerro Rico.

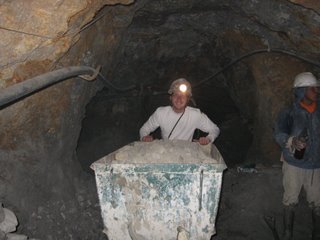

For the last 450 years, these mines have been bled of almost all their profitable minerals. Some estimates say that over eight million people have died over this time. Apart from the danger of falling rocks and dynamite explosions, the prevalence of silicosis, a pulmonary disease that eventually causes the lungs to burst, amongst those who work in the mines provides an additional threat. It is hard to imagine how awful these conditions truly are, but we were able to see a glimpse of this depressing life on a guided tour of the mines.

For the last 450 years, these mines have been bled of almost all their profitable minerals. Some estimates say that over eight million people have died over this time. Apart from the danger of falling rocks and dynamite explosions, the prevalence of silicosis, a pulmonary disease that eventually causes the lungs to burst, amongst those who work in the mines provides an additional threat. It is hard to imagine how awful these conditions truly are, but we were able to see a glimpse of this depressing life on a guided tour of the mines. Gualberto, four mamas, twelve children, and I took a ride up to Cerro Rico in the afternoon to visit the mines. Upon arriving at the base, we bought coca leaves, alcohol, cigarettes, and dynamite (it doesn’t look like the sticks you see in the movies) to give to the miners who often work twelve to fifteen hours a day. We then proceeded up the hill and found two miners who would guide us through the confusing labyrinth. It is not permitted to go without a guide, and for good reason. Once we were inside, it was as if we had entered another world, full of winding tunnels, tracks, and piles of rock. One of our guides told us that it was appropriate to give gifts to every group of miners who we talked to. The first group we encountered were mere boys, probably no older than sixteen. Shy at first, they came shooting out of their holes when we told them that we had soft drinks to share. The way that they gulped down these refreshments would make you think that we had given them something much more precious.

At the next station, about two hundred meters inside the mine, we came to a group of men who were banging away at a sheet of rock. Here we offered them dynamite, coca leaves, and cigarettes. They were happy to receive them, but were hoping for a bottle of alcohol. We told them that all we had were small bottles of rubbing alcohol to offer to El Tío.

Speaking of El Tío, it is worth explaining a little bit about the important role of this deity. El Tío is the miners’ representation of the devil and is thought to be the power that controls the fortune of the miners.

In every mine of Cerro Rico there is a statue of El Tío, and miners come daily to give offerings to him. Whether it be coca leaves, alcohol, or cigarettes, the miners believe that if they do not pay homage to El Tío, they will extract few minerals and may even die in an accident. When we visited El Tío, the mamás (some of whose parents had worked in the mines) were adamant about being respectful to him. In turn, we presented our offerings to El Tío and reflected in silence for several minutes. I then asked to take one of the mama’s pictures with El Tío, and she told me absolutely not. You may take a picture of him alone, but never with anyone else. Regardless of my own beliefs, I certainly did not want to offend traditional practices.

In every mine of Cerro Rico there is a statue of El Tío, and miners come daily to give offerings to him. Whether it be coca leaves, alcohol, or cigarettes, the miners believe that if they do not pay homage to El Tío, they will extract few minerals and may even die in an accident. When we visited El Tío, the mamás (some of whose parents had worked in the mines) were adamant about being respectful to him. In turn, we presented our offerings to El Tío and reflected in silence for several minutes. I then asked to take one of the mama’s pictures with El Tío, and she told me absolutely not. You may take a picture of him alone, but never with anyone else. Regardless of my own beliefs, I certainly did not want to offend traditional practices.

We spent another half-hour in the mines and then got escorted out of the muddy tunnels by our guides. On the way back, I stayed in the back with one of the guides and asked him about life in Cerro Rico. He, twenty-one years old, told me that he had been working for seven years in the mines and made about five dollars per day. Today, almost all of the silver has been extracted from the mines, and only in the deepest, most dangerous parts can you find small deposits. Other less valuable minerals and metals, such as tin, are now the principle extractions from the mines. In the hour and a half that we were in the mines, the heartbreaking existence of those who work there overwhelmed me. The tools and techniques that the miners use today have not changed much from a century ago, and the faces of these workers reveal the rigor of their labor.

We spent another half-hour in the mines and then got escorted out of the muddy tunnels by our guides. On the way back, I stayed in the back with one of the guides and asked him about life in Cerro Rico. He, twenty-one years old, told me that he had been working for seven years in the mines and made about five dollars per day. Today, almost all of the silver has been extracted from the mines, and only in the deepest, most dangerous parts can you find small deposits. Other less valuable minerals and metals, such as tin, are now the principle extractions from the mines. In the hour and a half that we were in the mines, the heartbreaking existence of those who work there overwhelmed me. The tools and techniques that the miners use today have not changed much from a century ago, and the faces of these workers reveal the rigor of their labor. Although I can attempt to describe my brief experience in the mines, I would encourage anyone interested in learning more about Cerro Rico to watch a documentary called “The Devil’s Miner.” You can get it at Blockbuster or on NetFlix, and it is incredibly powerful. After our trip, I showed it to the children in the Villa, and I think that some of them became very appreciative of the life and support that they have at Amistad.

Although I can attempt to describe my brief experience in the mines, I would encourage anyone interested in learning more about Cerro Rico to watch a documentary called “The Devil’s Miner.” You can get it at Blockbuster or on NetFlix, and it is incredibly powerful. After our trip, I showed it to the children in the Villa, and I think that some of them became very appreciative of the life and support that they have at Amistad. The visit to Cerro Rico was a moving and fitting conclusion to our trip to Potosí. The bus ride back to Cochabamba was much more comfortable, as we took a flota with fifty-seats. Interestingly, this larger bus only took nine hours to get back to the Villa. And upon arriving at five in the morning, we were all ready for a long nap. A journey to the highest city in the world can be quite exhausting.

For children in Cochabamba, February marks the end of summer vacation and the beginning of a month-long celebration called Carnaval. While the festivities do not officially begin until the 17th, children all over Bolivia use the 1st of February as the starting date for their reign of terror. Water balloons. They are absolutely everywhere. You cannot walk down any street in Cochabamba without feeling the threat of an armed and lurking delinquent ready to plant you one between the eyes. The youngest lads take it as simple fun, trying, mostly in vain, to hurl an overfilled balloon in the direction of an unsuspecting pedestrian. It’s the young adolescents that you have to be careful with. These misfits ride around in cars with a seemingly limitless arsenal of water balloons, searching for their victims. Walking along a side street on my way back from the Villa one afternoon, I found myself alone in just such a situation. What seemed like a common 1980´s Toyota pickup with four boys straddling the sides of the bed turned out to be a dangerous projectile launcher. The truck slowed down, and the boys began whistling and shouting things about a gringo(me). I knew that I was in the wrong place at the wrong time when the first water balloon narrowly missed my left shoulder and crashed into the wall behind me. This was no warning shot, I quickly discovered, but rather an attempt to injure a “maldito gringo”(again, me). The pieces of broken ice on the pavement betrayed these intentions. With little desire to find out what the next shot might contain within it, I began to run (oddly enough, toward my assailants).

As I passed by the truck, three more bullets fired toward me. Using my best Matrix techniques, I tried to contort my body away from harm. However, I am neither Neo nor Boris, and one of the shots found its mark on my right arm. The sting of the hard(frozen) sphere knocked me off balance and against the wall. Cursing the pain, I sprinted down the street, out-of-range of several more futile hurls. Either they had exhausted their ammo or been sufficiently satisfied with one direct hit, but the boys did not pursue me anymore. I am guessing that it was the latter, because their laughter was audible from a block away.

As I looked down at the red spot on my forearm, I thought to myself, Well it could have been worse. I remembered a story that a fellow American acquaintance had told me about her recent experience with the delinquency of Carnaval. When called over to a stopped car to give directions, she was welcomed with a face full of shaving cream. Another day, while riding on a city bus, I witnessed an unfortunate middle-aged woman get pelted in the side of the head with a water balloon. Lesson: regardless of how hot it may be, this month it is not advisable to lower the window on any public transportation vehicle.

As malicious as these stories may seem, I think they are more of the exception than the rule. Most children carrying water balloons seem more interested in playing with each other than bothering strangers. Who doesn’t love a good water fight? Even so, as the official celebration dates approach, you can be sure that I will be vigilant when in public. Who knows, I might even start packing some heat myself.